How Long Are The Federalist Papers

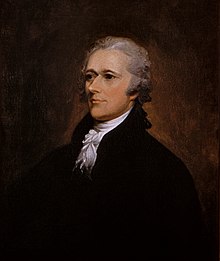

Title page of the first drove of The Federalist (1788). This item volume was a gift from Alexander Hamilton'due south married woman Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton to her sis Angelica | |

| Authors |

|

|---|---|

| Original title | The Federalist |

| Country | United states |

| Linguistic communication | English language |

| Publisher |

|

| Publication date | Oct 27, 1787 – May 28, 1788 |

| Media blazon |

|

The Federalist Papers is a collection of 85 articles and essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the collective pseudonym "Publius" to promote the ratification of the Constitution of the United States. The collection was commonly known as The Federalist until the proper name The Federalist Papers emerged in the 20th century.

The starting time 77 of these essays were published serially in the Independent Periodical, the New York Bundle, and The Daily Advertiser betwixt October 1787 and April 1788.[i] A compilation of these 77 essays and eight others were published in two volumes every bit The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, every bit Agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787 , by publishing house J. & A. McLean in March and May 1788.[2] [three] The last viii papers (Nos. 78–85) were republished in the New York newspapers between June fourteen and August 16, 1788.

The authors of The Federalist intended to influence the voters to ratify the Constitution. In Federalist No. one, they explicitly set that debate in broad political terms:

It has been often remarked, that it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, past their conduct and example, to make up one's mind the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not, of establishing adept government from reflection and selection, or whether they are forever destined to depend, for their political constitutions, on blow and strength.[4]

In Federalist No. ten, Madison discusses the means of preventing rule past majority faction and advocates a large, commercial commonwealth. This is complemented by Federalist No. 14, in which Madison takes the measure of the The states, declares it advisable for an extended commonwealth, and concludes with a memorable defence of the constitutional and political inventiveness of the Federal Convention.[v]

In Federalist No. 84, Hamilton makes the case that there is no demand to amend the Constitution past calculation a Pecker of Rights, insisting that the various provisions in the proposed Constitution protecting liberty amount to a "bill of rights."[6] Federalist No. 78, too written by Hamilton, lays the groundwork for the doctrine of judicial review by federal courts of federal legislation or executive acts. Federalist No. seventy presents Hamilton's case for a i-man chief executive. In Federalist No. 39, Madison presents the clearest exposition of what has come up to be chosen "Federalism". In Federalist No. 51, Madison distills arguments for checks and balances in an essay often quoted for its justification of government every bit "the greatest of all reflections on homo nature." According to historian Richard B. Morris, the essays that make up The Federalist Papers are an "unequalled exposition of the Constitution, a classic in political science unsurpassed in both breadth and depth by the product of any later American writer."[7]

On June 21, 1788, the proposed Constitution was ratified by the minimum of ix states required under Article Seven. Towards the cease of July 1788, with eleven states having ratified the new Constitution, the process of organizing the new government began.[ commendation needed ]

History [edit]

Origins [edit]

The Federal Convention (Constitutional Convention) sent the proposed Constitution to the Confederation Congress, which in turn submitted it to the states for ratification at the cease of September 1787. On September 27, 1787, "Cato" first appeared in the New York press criticizing the proposition; "Brutus" followed on Oct 18, 1787.[8] These and other articles and public letters critical of the new Constitution would eventually get known as the "Anti-Federalist Papers". In response, Alexander Hamilton decided to launch a measured defence and extensive caption of the proposed Constitution to the people of the state of New York. He wrote in Federalist No. 1 that the series would "endeavor to requite a satisfactory respond to all the objections which shall have made their appearance, that may seem to have any claim to your attention."[nine]

Hamilton recruited collaborators for the project. He enlisted John Jay, who later on four stiff essays (Federalist Nos. 2, three, 4, and five), barbarous sick and contributed just one more essay, Federalist No. 64, to the series. Jay besides distilled his instance into a pamphlet in the spring of 1788, An Address to the People of the Land of New-York;[10] Hamilton cited information technology approvingly in Federalist No. 85. James Madison, nowadays in New York as a Virginia delegate to the Confederation Congress, was recruited past Hamilton and Jay and became Hamilton's primary collaborator. Gouverneur Morris and William Duer were also considered. All the same, Morris turned down the invitation, and Hamilton rejected three essays written by Duer.[xi] Duer after wrote in back up of the three Federalist authors under the name "Philo-Publius", meaning either "Friend of the People" or "Friend of Hamilton" based on Hamilton'south pen name Publius.

Alexander Hamilton chose the pseudonymous name "Publius". While many other pieces representing both sides of the ramble debate were written under Roman names, historian Albert Furtwangler contends that "'Publius' was a cut to a higher place 'Caesar' or 'Brutus' or fifty-fifty 'Cato'. Publius Valerius helped found the ancient republic of Rome. His more than famous name, Publicola, meant 'friend of the people'."[12] Hamilton had practical this pseudonym to three letters in 1778, in which he attacked fellow Federalist Samuel Hunt and revealed that Chase had taken advantage of knowledge gained in Congress to try to boss the flour market.[12]

[edit]

James Madison, Hamilton's major collaborator, subsequently 4th President of the The states (1809-1817)

At the time of publication, the authors of The Federalist Papers attempted to hibernate their identities due to Hamilton and Madison having attended the convention.[xiii] Acute observers, even so, correctly discerned the identities of Hamilton, Madison, and Jay. Establishing authorial authenticity of the essays that constitute The Federalist Papers has not always been clear. Later Alexander Hamilton died in 1804, a list emerged, claiming that he alone had written 2-thirds of The Federalist essays. Some believe that several of these essays were written past James Madison (Nos. 49–58 and 62–63). The scholarly detective piece of work of Douglass Adair in 1944 postulated the following assignments of authorship, corroborated in 1964 by a computer analysis of the text:[14]

- Alexander Hamilton (51 articles: Nos. 1, 6–ix, 11–13, 15–17, 21–36, 59–61, and 65–85)

- James Madison (29 articles: Nos. 10, 14, 18–20,[fifteen] 37–58 and 62–63)

- John Jay (5 articles: Nos. 2–5 and 64).

In vi months, a total of 85 manufactures were written by the three men. Hamilton, who had been a leading advocate of national constitutional reform throughout the 1780s and was one of the iii representatives for New York at the Constitutional Convention, in 1789 became the offset Secretary of the Treasury, a post he held until his resignation in 1795. Madison, who is now best-selling as the father of the Constitution — despite his repeated rejection of this accolade during his lifetime,[16] became a leading member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia (1789–1797), Secretary of Country (1801–1809), and ultimately the 4th President of the United States (1809–1817).[17]

John Jay, who had been secretarial assistant for foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation from 1784 through their expiration in 1789, became the first Chief Justice of the United States in 1789, stepping downward in 1795 to take election as governor of New York, a post he held for two terms, retiring in 1801.[ citation needed ]

Publication [edit]

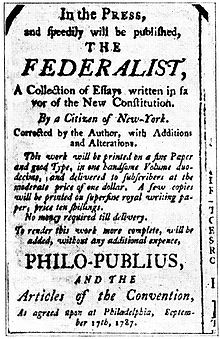

An advertisement for the book edition of The Federalist

The Federalist articles appeared in three New York newspapers: The Independent Journal, the New-York Packet, and the Daily Advertiser, beginning on October 27, 1787. Although written and published with haste, The Federalist articles were widely read and greatly influenced the shape of American political institutions.[18] Hamilton, Madison and Jay published the essays at a rapid footstep. At times, 3 to four new essays past Publius appeared in the papers in a single week. Garry Wills observes that this fast pace of production "overwhelmed" any possible response: "Who, given aplenty time could have answered such a battery of arguments? And no time was given."[19] Hamilton also encouraged the reprinting of the essays in newspapers exterior New York state, and indeed they were published in several other states where the ratification debate was taking place. Yet, they were only irregularly published exterior New York, and in other parts of the country they were ofttimes overshadowed by local writers.[20]

Considering the essays were initially published in New York, nigh of them begin with the same salutation: "To the People of the Country of New York".

The high need for the essays led to their publication in a more permanent class. On January 1, 1788, the New York publishing firm J. & A. McLean announced that they would publish the get-go 36 essays every bit a leap volume; that volume was released on March 22, 1788, and was titled The Federalist Volume i.[ane] New essays continued to appear in the newspapers; Federalist No. 77 was the last number to appear starting time in that course, on April ii. A 2d jump book was released on May 28, containing Federalist Nos. 37–77 and the previously unpublished Nos. 78–85.[ane] The final viii papers (Nos. 78–85) were republished in the New York newspapers between June fourteen and Baronial 16, 1788.[one] [xviii]

A 1792 French edition concluded the collective anonymity of Publius, announcing that the piece of work had been written by "Mm. Hamilton, Maddisson e Gay, citoyens de 50'État de New York".[21] In 1802, George Hopkins published an American edition that similarly named the authors. Hopkins wished as well that "the proper name of the writer should be prefixed to each number," but at this point Hamilton insisted that this was not to be, and the division of the essays among the 3 authors remained a secret.[22]

The first publication to divide the papers in such a style was an 1810 edition that used a list left by Hamilton to associate the authors with their numbers; this edition appeared every bit two volumes of the compiled "Works of Hamilton". In 1818, Jacob Gideon published a new edition with a new list of authors, based on a list provided by Madison. The difference between Hamilton'due south listing and Madison's formed the basis for a dispute over the authorship of a dozen of the essays.[23]

Both Hopkins's and Gideon's editions incorporated significant edits to the text of the papers themselves, generally with the approval of the authors. In 1863, Henry Dawson published an edition containing the original text of the papers, arguing that they should be preserved as they were written in that item historical moment, not every bit edited by the authors years later.[24]

Modernistic scholars generally apply the text prepared by Jacob E. Cooke for his 1961 edition of The Federalist; this edition used the newspaper texts for essay numbers 1–76 and the McLean edition for essay numbers 77–85.[25]

Disputed essays [edit]

John Jay, author of five of The Federalist Papers, afterwards became the commencement Chief Justice of the United States

While the authorship of 73 of The Federalist essays is fairly certain, the identities of those who wrote the twelve remaining essays are disputed by some scholars. The mod consensus is that Madison wrote essays Nos. 49–58, with Nos. 18–20 beingness products of a collaboration between him and Hamilton; No. 64 was by John Jay. The beginning open up designation of which essay belonged to whom was provided by Hamilton who, in the days before his ultimately fatal gun duel with Aaron Burr, provided his lawyer with a list detailing the author of each number. This list credited Hamilton with a full 63 of the essays (three of those being jointly written with Madison), almost three-quarters of the whole, and was used as the basis for an 1810 printing that was the kickoff to make specific attribution for the essays.[26]

Madison did not immediately dispute Hamilton'due south listing, simply provided his own list for the 1818 Gideon edition of The Federalist. Madison claimed 29 essays for himself, and he suggested that the deviation betwixt the ii lists was "owing doubtless to the hurry in which [Hamilton's] memorandum was fabricated out." A known error in Hamilton'due south list—Hamilton incorrectly ascribed No. 54 to John Jay, when in fact, Jay wrote No. 64—provided some evidence for Madison's suggestion.[27]

Statistical analysis has been undertaken on several occasions in attempts to accurately identify the author of each individual essay. Afterward examining word choice and writing style, studies mostly hold that the disputed essays were written by James Madison. However, in that location are notable exceptions maintaining that some of the essays which are now widely attributed to Madison were, in fact, collaborative efforts.[14] [28] [29]

Influence on the ratification debates [edit]

The Federalist Papers were written to support the ratification of the Constitution, specifically in New York. Whether they succeeded in this mission is questionable. Separate ratification proceedings took place in each state, and the essays were non reliably reprinted outside of New York; furthermore, by the time the series was well underway, a number of of import states had already ratified it, for instance Pennsylvania on December 12. New York held out until July 26; certainly The Federalist was more important there than anywhere else, merely Furtwangler argues that information technology "could hardly rival other major forces in the ratification contests"—specifically, these forces included the personal influence of well-known Federalists, for case Hamilton and Jay, and Anti-Federalists, including Governor George Clinton.[30] Further, past the time New York came to a vote, ten states had already ratified the Constitution and it had thus already passed—only nine states had to ratify it for the new government to be established amidst them; the ratification past Virginia, the tenth country, placed pressure on New York to ratify. In light of that, Furtwangler observes, "New York'southward refusal would make that state an odd outsider."[31]

Only 19 Federalists were elected to New York'south ratification convention, compared to the Anti-Federalists' 46 delegates. While New York did indeed ratify the Constitution on July 26, the lack of public support for pro-Constitution Federalists has led historian John Kaminski to suggest that the impact of The Federalist on New York citizens was "negligible".[32]

Every bit for Virginia, which ratified the Constitution only at its convention on June 25, Hamilton writes in a letter to Madison that the collected edition of The Federalist had been sent to Virginia; Furtwangler presumes that it was to human action as a "debater'southward handbook for the convention there", though he claims that this indirect influence would exist a "dubious stardom".[33] Probably of greater importance to the Virginia argue, in any instance, were George Washington's support for the proposed Constitution and the presence of Madison and Edmund Randolph, the governor, at the convention arguing for ratification.

Construction and content [edit]

In Federalist No. i, Hamilton listed half-dozen topics to be covered in the subsequent articles:

- "The utility of the Spousal relationship to your political prosperity"—covered in No. 2 through No. 14

- "The insufficiency of the present Confederation to preserve that Matrimony"—covered in No. 15 through No. 22

- "The necessity of a government at least equally energetic with the ane proposed to the attainment of this object"—covered in No. 23 through No. 36

- "The conformity of the proposed constitution to the truthful principles of republican government"—covered in No. 37 through No.

- "Its analogy to your ain state constitution"—covered in No. 85

- "The boosted security which its adoption will afford to the preservation of that species of government, to liberty and to prosperity"—covered in No. 85.[34]

Furtwangler notes that as the series grew, this plan was somewhat changed. The quaternary topic expanded into detailed coverage of the individual articles of the Constitution and the institutions information technology mandated, while the two last topics were merely touched on in the last essay.

The papers can be cleaved down past writer as well every bit by topic. At the start of the series, all three authors were contributing; the kickoff 20 papers are cleaved downwards as xi by Hamilton, five past Madison and four by Jay. The rest of the series, still, is dominated by three long segments by a single writer: Nos. 21–36 by Hamilton, Nos. 37–58 past Madison, written while Hamilton was in Albany, and No. 65 through the stop by Hamilton, published after Madison had left for Virginia.[35]

Opposition to the Bill of Rights [edit]

The Federalist Papers (specifically Federalist No. 84) are notable for their opposition to what later became the United States Bill of Rights. The idea of adding a Bill of Rights to the Constitution was originally controversial because the Constitution, as written, did non specifically enumerate or protect the rights of the people, rather it listed the powers of the regime and left all that remained to the states and the people. Alexander Hamilton, the author of Federalist No. 84, feared that such an enumeration, once written downward explicitly, would later be interpreted as a list of the only rights that people had.[ citation needed ]

However, Hamilton's opposition to a Bill of Rights was far from universal. Robert Yates, writing under the pseudonym "Brutus", articulated this view point in the so-called Anti-Federalist No. 84, asserting that a government unrestrained past such a bill could hands devolve into tyranny. References in The Federalist and in the ratification debates warn of demagogues of the diverseness who through divisive appeals would aim at tyranny. The Federalist begins and ends with this consequence.[36] In the final paper Hamilton offers "a lesson of moderation to all sincere lovers of the Matrimony, and ought to put them on their baby-sit against hazarding anarchy, ceremonious war, a perpetual breach of the States from each other, and possibly the military despotism of a successful demagogue".[37] The matter was further clarified past the Ninth Amendment.

Judicial use [edit]

Federal judges, when interpreting the Constitution, frequently use The Federalist Papers as a contemporary account of the intentions of the framers and ratifiers.[38] They have been applied on bug ranging from the power of the federal government in strange diplomacy (in Hines v. Davidowitz) to the validity of ex mail facto laws (in the 1798 conclusion Calder v. Bull, apparently the kickoff decision to mention The Federalist).[39] By 2000[update], The Federalist had been quoted 291 times in Supreme Courtroom decisions.[40]

The corporeality of deference that should be given to The Federalist Papers in ramble interpretation has always been somewhat controversial. As early every bit 1819, Chief Justice John Marshall noted in the famous case McCulloch v. Maryland, that "the opinions expressed by the authors of that piece of work accept been justly supposed to be entitled to great respect in expounding the Constitution. No tribute can exist paid to them which exceeds their merit; merely in applying their opinions to the cases which may ascend in the progress of our regime, a right to guess of their definiteness must be retained."[41] In a letter to Thomas Ritchie in 1821, James Madison stated of the Constitution that "the legitimate meaning of the Musical instrument must be derived from the text itself; or if a fundamental is to be sought elsewhere, it must exist not in the opinions or intentions of the Body which planned & proposed the Constitution, but in the sense fastened to information technology by the people in their respective State Conventions where it recd. all the authority which information technology possesses."[42] [43]

Consummate list [edit]

The colors used to highlight the rows correspond to the author of the paper.

| # | Date | Championship | Author |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | October 27, 1787 | Full general Introduction | Alexander Hamilton |

| 2 | October 31, 1787 | Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence | John Jay |

| 3 | November three, 1787 | The Same Subject Continued: Apropos Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence | John Jay |

| 4 | November vii, 1787 | The Same Subject Connected: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence | John Jay |

| five | November 10, 1787 | The Same Subject Connected: Apropos Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence | John Jay |

| half dozen | Nov 14, 1787 | Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between the States | Alexander Hamilton |

| 7 | Nov fifteen, 1787 | The Aforementioned Subject Connected: Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between u.s. | Alexander Hamilton |

| 8 | November twenty, 1787 | The Consequences of Hostilities Between the States | Alexander Hamilton |

| ix | November 21, 1787 | The Utility of the Union equally a Safeguard Confronting Domestic Faction and Insurrection | Alexander Hamilton |

| ten | Nov 22, 1787 | The Aforementioned Discipline Continued: The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection | James Madison |

| 11 | November 24, 1787 | The Utility of the Spousal relationship in Respect to Commercial Relations and a Navy | Alexander Hamilton |

| 12 | November 27, 1787 | The Utility of the Wedlock In Respect to Revenue | Alexander Hamilton |

| 13 | November 28, 1787 | Advantage of the Union in Respect to Economic system in Regime | Alexander Hamilton |

| fourteen | November 30, 1787 | Objections to the Proposed Constitution From Extent of Territory Answered | James Madison |

| fifteen | December 1, 1787 | The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union | Alexander Hamilton |

| sixteen | Dec four, 1787 | The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Nowadays Confederation to Preserve the Spousal relationship | Alexander Hamilton |

| 17 | December 5, 1787 | The Aforementioned Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union | Alexander Hamilton |

| 18 | December seven, 1787 | The Same Discipline Connected: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union | James Madison[15] |

| 19 | December 8, 1787 | The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Nowadays Confederation to Preserve the Wedlock | James Madison[15] |

| twenty | December 11, 1787 | The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union | James Madison[fifteen] |

| 21 | Dec 12, 1787 | Other Defects of the Present Confederation | Alexander Hamilton |

| 22 | December 14, 1787 | The Same Subject area Continued: Other Defects of the Present Confederation | Alexander Hamilton |

| 23 | December eighteen, 1787 | The Necessity of a Government as Energetic as the One Proposed to the Preservation of the Union | Alexander Hamilton |

| 24 | December nineteen, 1787 | The Powers Necessary to the Common Defense Further Considered | Alexander Hamilton |

| 25 | December 21, 1787 | The Same Subject Continued: The Powers Necessary to the Common Defense Further Considered | Alexander Hamilton |

| 26 | December 22, 1787 | The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Mutual Defence force Considered | Alexander Hamilton |

| 27 | December 25, 1787 | The Same Subject Continued: The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Dominance in Regard to the Common Defence force Considered | Alexander Hamilton |

| 28 | December 26, 1787 | The Same Subject Continued: The Thought of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense force Considered | Alexander Hamilton |

| 29 | January 9, 1788 | Concerning the Militia | Alexander Hamilton |

| 30 | December 28, 1787 | Concerning the General Power of Taxation | Alexander Hamilton |

| 31 | January 1, 1788 | The Same Subject Continued: Apropos the General Power of Taxation | Alexander Hamilton |

| 32 | January 2, 1788 | The Same Field of study Connected: Apropos the General Ability of Tax | Alexander Hamilton |

| 33 | January two, 1788 | The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the Full general Power of Taxation | Alexander Hamilton |

| 34 | January five, 1788 | The Same Subject area Continued: Concerning the Full general Power of Taxation | Alexander Hamilton |

| 35 | Jan 5, 1788 | The Same Subject area Connected: Concerning the General Power of Tax | Alexander Hamilton |

| 36 | January 8, 1788 | The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation | Alexander Hamilton |

| 37 | Jan 11, 1788 | Concerning the Difficulties of the Convention in Devising a Proper Form of Regime | James Madison |

| 38 | January 12, 1788 | The Aforementioned Subject Connected, and the Incoherence of the Objections to the New Plan Exposed | James Madison |

| 39 | January 16, 1788 | The Conformity of the Plan to Republican Principles | James Madison |

| forty | January 18, 1788 | The Powers of the convention to Class a Mixed Government Examined and Sustained | James Madison |

| 41 | January 19, 1788 | General View of the Powers Conferred past the Constitution | James Madison |

| 42 | January 22, 1788 | The Powers Conferred by the Constitution Further Considered | James Madison |

| 43 | January 23, 1788 | The Same Subject Continued: The Powers Conferred past the Constitution Farther Considered | James Madison |

| 44 | January 25, 1788 | Restrictions on the Authority of the Several States | James Madison |

| 45 | January 26, 1788 | The Alleged Danger From the Powers of the Spousal relationship to the Country Governments Considered | James Madison |

| 46 | January 29, 1788 | The Influence of the State and Federal Governments Compared | James Madison |

| 47 | January thirty, 1788 | The Particular Structure of the New Authorities and the Distribution of Power Among Its Dissimilar Parts | James Madison |

| 48 | Feb 1, 1788 | These Departments Should Not Exist Then Far Separated as to Accept No Constitutional Control Over Each Other | James Madison |

| 49 | Feb 2, 1788 | Method of Guarding Against the Encroachments of Any I Section of Government | James Madison[44] |

| 50 | February 5, 1788 | Periodic Appeals to the People Considered | James Madison[44] |

| 51 | February 6, 1788 | The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments | James Madison[44] |

| 52 | Feb viii, 1788 | The House of Representatives | James Madison[44] |

| 53 | February 9, 1788 | The Same Subject Connected: The Business firm of Representatives | James Madison[44] |

| 54 | Feb 12, 1788 | The Apportionment of Members Among the States | James Madison[44] |

| 55 | February 13, 1788 | The Full Number of the Business firm of Representatives | James Madison[44] |

| 56 | February sixteen, 1788 | The Aforementioned Subject Connected: The Total Number of the Business firm of Representatives | James Madison[44] |

| 57 | Feb 19, 1788 | The Alleged Tendency of the New Plan to Elevate the Few at the Expense of the Many | James Madison[44] |

| 58 | February 20, 1788 | Objection That The Number of Members Will Non Be Augmented every bit the Progress of Population Demands Considered | James Madison[44] |

| 59 | Feb 22, 1788 | Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members | Alexander Hamilton |

| 60 | February 23, 1788 | The Same Field of study Continued: Concerning the Ability of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members | Alexander Hamilton |

| 61 | February 26, 1788 | The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members | Alexander Hamilton |

| 62 | February 27, 1788 | The Senate | James Madison[44] |

| 63 | March 1, 1788 | The Senate Connected | James Madison[44] |

| 64 | March 5, 1788 | The Powers of the Senate | John Jay |

| 65 | March 7, 1788 | The Powers of the Senate Connected | Alexander Hamilton |

| 66 | March eight, 1788 | Objections to the Power of the Senate To Set every bit a Court for Impeachments Further Considered | Alexander Hamilton |

| 67 | March xi, 1788 | The Executive Department | Alexander Hamilton |

| 68 | March 12, 1788 | The Mode of Electing the President | Alexander Hamilton |

| 69 | March xiv, 1788 | The Existent Grapheme of the Executive | Alexander Hamilton |

| 70 | March 15, 1788 | The Executive Department Further Considered | Alexander Hamilton |

| 71 | March 18, 1788 | The Duration in Office of the Executive | Alexander Hamilton |

| 72 | March nineteen, 1788 | The Same Discipline Connected, and Re-Eligibility of the Executive Considered | Alexander Hamilton |

| 73 | March 21, 1788 | The Provision For The Back up of the Executive, and the Veto Power | Alexander Hamilton |

| 74 | March 25, 1788 | The Command of the Military and Naval Forces, and the Pardoning Power of the Executive | Alexander Hamilton |

| 75 | March 26, 1788 | The Treaty Making Ability of the Executive | Alexander Hamilton |

| 76 | April 1, 1788 | The Appointing Power of the Executive | Alexander Hamilton |

| 77 | April 2, 1788 | The Appointing Power Continued and Other Powers of the Executive Considered | Alexander Hamilton |

| 78 | May 28, 1788 (book) June 14, 1788 (paper) | The Judiciary Department | Alexander Hamilton |

| 79 | May 28, 1788 (book) June 18, 1788 (paper) | The Judiciary Continued | Alexander Hamilton |

| 80 | June 21, 1788 | The Powers of the Judiciary | Alexander Hamilton |

| 81 | June 25, 1788; June 28, 1788 | The Judiciary Continued, and the Distribution of the Judicial Authority | Alexander Hamilton |

| 82 | July 2, 1788 | The Judiciary Continued | Alexander Hamilton |

| 83 | July 5, 1788; July 9, 1788; July 12, 1788 | The Judiciary Continued in Relation to Trial by Jury | Alexander Hamilton |

| 84 | July sixteen, 1788; July 26, 1788; August ix, 1788 | Certain General and Miscellaneous Objections to the Constitution Considered and Answered | Alexander Hamilton |

| 85 | August 13, 1788; August 16, 1788 | Concluding Remarks | Alexander Hamilton |

In pop culture [edit]

The purposes and authorship of The Federalist Papers were prominently highlighted in the lyrics of "Non-End", the finale of Human activity I in the 2015 Broadway musical Hamilton, written past Lin-Manuel Miranda.[45]

See also [edit]

- American philosophy

- The Anti-Federalist Papers

- The Consummate Anti-Federalist

- List of pseudonyms used in the American Constitutional debates

Citations [edit]

- ^ a b c d Lloyd, Gordon. "Introduction to the Federalist". teachingamericanhistory.org. Archived from the original on 2018-06-eighteen. Retrieved 2018-06-xviii .

- ^ The Federalist: a Drove of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, equally Agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787, in two volumes (1st ed.). New York: J. & A. McLean. 1788. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16 – via Library of Congress.

- ^ Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York Urban center. New-York Historical Club. Yale Academy Press. p. 194. ISBN978-0-300-05536-8.

- ^ The Federalist Papers . Toronto: Bantam Books. 1982.

- ^ Wills, x.

- ^ Hamilton, Alexander (2020). The federalist papers. John Jay, James Madison. New York, NY: Open Road Integrated Media. ISBN978-1-5040-6099-eight. OCLC 1143829765.

- ^ Richard B. Morris, The Forging of the Union: 1781–1789 (1987) p. 309

- ^ Furtwangler, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Gunn, Giles B. (1994). Early American Writing. Penguin Classics. p. 540. ISBN978-0-14-039087-2.

- ^ Jay, John. "An Address to the People of the State of New-York". columbia.edu. Columbia Academy Libraries. Archived from the original on 2010-06-27. Excerpted from: Elliot, Jonathan, ed. (1836–1859). The debates in the several state conventions on the adoption of the Federal Constitution: every bit recommended past the general convention at Philadelphia, in 1787 (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co.; Washington: Taylor & Maury. OCLC 656425.

- ^ Furtwangler, pp. 51–56.

- ^ a b Furtwangler, p. 51.

- ^ Barendt, Eric (2016). Anonymous Speech communication: Literature, Police force and Politics. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 38. ISBN9781509904075.

- ^ a b Mosteller, Frederick; Wallace, David L. (2012). Practical Bayesian and Classical Inference: The Instance of The Federalist Papers. Springer Scientific discipline & Business Media. ISBN978-1-4612-5256-6.

- ^ a b c d Nos. 18, 19, twenty are oftentimes indicated as being jointly written by Hamilton and Madison. However, Adair concurs with previous historians that these are Madison'southward writing alone: "Madison had certainly written all of the essays himself, including in revised form only a pocket-sized amount of pertinent information submitted by Hamilton from his rather sketchy inquiry on the same subject." Adair, 63.

- ^ Banning, Lance. James Madison: Federalist, annotation one. Archived 2018-01-13 at the Wayback Automobile.

- ^ Come across, e.g., Ralph Ketcham, James Madison. New York: Macmillan, 1971; reprint ed., Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998. See also Irving N. Brant, James Madison: Father of the Constitution, 1787–1800. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1950.

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica (2007). Founding Fathers: The Essential Guide to the Men Who Fabricated America. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN978-0-470-11792-7.

- ^ Wills, xii.

- ^ Furtwangler, p. 20.

- ^ Bain, Robert (1977). "The Federalist". In Emerson, Everett H. (ed.). American Literature, 1764-1789: The Revolutionary Years. Univ. of Wisconsin Printing. p. 260. ISBN978-0-299-07270-4.

- ^ Adair, 40–41.

- ^ Adair, 44–46.

- ^ Lodge, Henry Cabot, ed. (1902). The Federalist, a Commentary on the Constitution of the Usa. Putnam. pp. xxxviii–xliii. Retrieved 2009-02-xvi .

- ^ Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison (Jacob E. Cooke, ed., The Federalist (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan Academy Press, 1961 and later reprintings). ISBN 978-0-8195-6077-three.

- ^ Adair, 46–48.

- ^ Adair, 48.

- ^ Collins, Jeff; Kaufer, David; Vlachos, Pantelis; Butler, Brian; Ishizaki, Suguru (February 2004). "Detecting Collaborations in Text: Comparing the Authors' Rhetorical Language Choices in The Federalist Papers". Computers and the Humanities. 38 (one): xv–36. CiteSeerX10.i.1.459.8655. doi:10.1023/B:CHUM.0000009291.06947.52. S2CID 207680270.

- ^ Fung, Glenn (2003). "The Disputed Federalist Papers: SVM Feature Option via Concave Minimization" (PDF). Periodical of the ACM. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2005-04-17.

- ^ Furtwangler, p. 21.

- ^ Furtwangler, p. 22.

- ^ Coenen, Dan. "Fifteen Curious Facts nearly The Federalist Papers". Media Eatables. Archived from the original on 2013-01-15. Retrieved 2012-12-05 .

- ^ Furtwangler, p. 23.

- ^ This scheme of division is adjusted from Charles K. Kesler's introduction to The Federalist Papers (New York: Signet Classic, 1999) pp. 15–17. A similar segmentation is indicated by Furtwangler, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Wills, 274.

- ^ Tulis, Jeffrey (1987). The Rhetorical Presidency . Princeton Academy Press. p. 30. ISBN978-0-691-02295-6.

- ^ Harvey Flaumenhaft, "Hamilton's Administrative Republic and the American Presidency," in The Presidency in the Ramble Lodge, ed. Joseph M. Bessette and Jeffrey K. Tulis (Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana Land University Press, 1981), 65–114.

- ^ Lupu, Ira C.; "The Near-Cited Federalist Papers". Constitutional Commentary (1998) pp. 403+; using Supreme Court citations, the 5 well-nigh cited were Federalist No. 42 (Madison) (33 decisions), Federalist No. 78 (Hamilton) (30 decisions), Federalist No. 81 (Hamilton) (27 decisions), Federalist No. 51 (Madison) (26 decisions), Federalist No. 32 (Hamilton) (25 decisions).

- ^ See, amongst others, a very early exploration of the judicial use of The Federalist in Charles W. Pierson, "The Federalist in the Supreme Court", The Yale Law Periodical, Vol. 33, No. 7. (May 1924), pp. 728–35.

- ^ Chernow, Ron. "Alexander Hamilton". Penguin Books, 2004. (p. 260)

- ^ Arthur, John (1995). Words That Demark: Judicial Review and the Grounds of Modern Constitutional Theory . Westview Printing. pp. 41. ISBN978-0-8133-2349-seven.

- ^ Madison to Thomas Ritchie, September 15, 1821. Quoted in Furtwangler, p. 36.

- ^ Max Farrand, ed. (1911). The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787. Yale Academy Printing.

the legitimate meaning of the Instrument must exist derived from the text itself.

- ^ a b c d east f g h i j k l Ane of twelve disputed papers (Nos. 49–58 and 62–63) to which both Madison and Hamilton laid claim. See Adair, 93. Modern scholarly consensus leans towards Madison as the writer of all twelve, and he is and then credited in this tabular array.

- ^ Miranda, Lin-Manuel; McCarter, Jeremy (2016). Hamilton: The Revolution. M Key Publishing. pp. 142–143. ISBN978-one-4555-6753-9.

General and cited references [edit]

- Adair, Douglass (1974). "The Disputed Federalist Papers". Fame and the Founding Fathers. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

- Mosteller, Frederick; Wallace, David 50. (2012). Practical Bayesian and Classical Inference: The Case of The Federalist Papers. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN978-1-4612-5256-6. Updated 2nd ed., originally published as Mosteller, Frederick; Wallace, David L. (June 1963). "Inference in an Authorship Problem". Periodical of the American Statistical Association. 58 (302): 275–309. JSTOR 2283270.

- Furtwangler, Albert (1984). The Authority of Publius: A Reading of the Federalist Papers. Ithaca, New York: Cornell Univ. Press. ISBN978-0-8014-9339-3.

- Wills, Gary. Explaining America: The Federalist. Garden City, NJ: 1981.

Further reading [edit]

- Bradley, Harold W. (November 1945). "The Political Thinking of George Washington". The Journal of Southern History. Southern Historical Clan. xi (4): 469–486. doi:10.2307/2198308. JSTOR 2198308.

- Dietze, Gottfried. The Federalist: A Classic on Federalism and Costless Government. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1960.

- Epstein, David F. The Political Theory of the Federalist. Chicago: The Academy of Chicago Printing, 1984.

- Everdell, William R. (2000). The End of Kings: A History of Republics and Republicans . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Fischer, David Hackett (1965). The Revolution of American Conservatism: The Federalist Party in the Era of Jeffersonian Democracy . Harper & Row.

- Gray, Leslie, and Wynell Burroughs. "Educational activity With Documents: Ratification of the Constitution". Social Education, 51 (1987): 322–24.

- Hamilton, Alexander; Madison, James; Jay, John (1901). Smith, Goldwin (ed.). The Federalist (PDF). New York: The Colonial Printing.

- Heriot, Gail. "Are Modernistic Bloggers Following in the Footsteps of Publius (and Other Musings on Blogging By Legal Scholars)", 84 Wash. U. 50. Rev. 1113 (2006).

- Hofstadter, Richard (1969). The Idea of a Political party System: The Ascent of Legitimate Opposition in the Usa, 1780-1840 . University of California Press. ISBN978-0-5200-1754-two.

- Kesler, Charles R. Saving the Revolution: The Federalist Papers and the American Founding. New York: 1987.

- Meyerson, Michael I. (2008). Liberty's Blueprint: How Madison and Hamilton Wrote the Federalist Papers, Divers the Constitution, and Made Republic Rubber for the World. New York: Basic Books.

- Patrick, John J., and Clair W. Keller. Lessons on the Federalist Papers: Supplements to High School Courses in American History, Government and Civics. Bloomington, IN: Organization of American Historians in clan with ERIC/ChESS, 1987. ED 280 764.

- Schechter, Stephen L. Teaching about American Federal Republic. Philadelphia: Heart for the Study of Federalism at Temple University, 1984. ED 248 161.

- Scott, Kyle. The Federalist Papers: A Reader's Guide (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2013).

- Sunstein, Cass R. "The Enlarged Republic—Then and Now", The New York Review of Books (March 26, 2009): Volume LVI, Number 5, p. 45.

- Webster, Mary E. The Federalist Papers: In Modern Language Indexed for Today'southward Political Issues. Bellevue, WA: Merril Press, 1999.

- White, Morton. Philosophy, The Federalist, and the Constitution. New York: 1987.

- Whitten, Roger D. (ed.). The Federalist Papers, or, How Government Is Supposed to Work, "Edited for Readability". Oakesdale, WA: Lucky Zebra Press, 2007. ISBN 9780979956508. OCLC 243605493.

External links [edit]

- The Federalist Papers at Standard Ebooks

- "The federalist: a collection of essays"

- "Full Text of The Federalist Papers"

- The Federalist Papers, original 1788 printing

- The Federalist Papers at Project Gutenberg

- National Archives on The Federalist

- The Federalist Papers on the Bill of Rights

- Teaching The Federalist Papers

- Booknotes interview with Robert Scigliano on Scigliano's Modernistic Library edition of The Federalist Papers, January 21, 2001.

- Collection of The Federalist Papers

- EDSITEment on The Federalist and Anti-Federalist debates on multifariousness and the extended republic

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

-

The Federalist Papers public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Federalist Papers public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Federalist_Papers

Posted by: bennettweland.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Long Are The Federalist Papers"

Post a Comment